Welcome to The Pitch. Join filmmaker and VC member Kate Villevoye as she sits down with commissioners from leading international media platforms. Get an inside look at each platform’s editorial process and discover what collaborative opportunities exist so you can nail your next story pitch.

The Essentials:

Platform: LABOCINE

Senior Editor: Alexis Gambis

Content Type: Curated streaming platform and digital magazine at the crossroads of science and film

Editorial Themes: Science-driven narratives, experimental storytelling, interdisciplinary explorations, and films that illuminate the human side of scientific inquiry

Ideal Video Format: Short films, features, experimental works, and hybrid genres that creatively engage with scientific themes

Pitches/Submissions Considered? Open to completed films, works-in-progress, and proposals that align with LABOCINE’s mission

Where to submit: here

Learn more: here

Kate Villevoye: Alexis, thank you for talking to us about LABOCINE! What inspired you to create this platform?

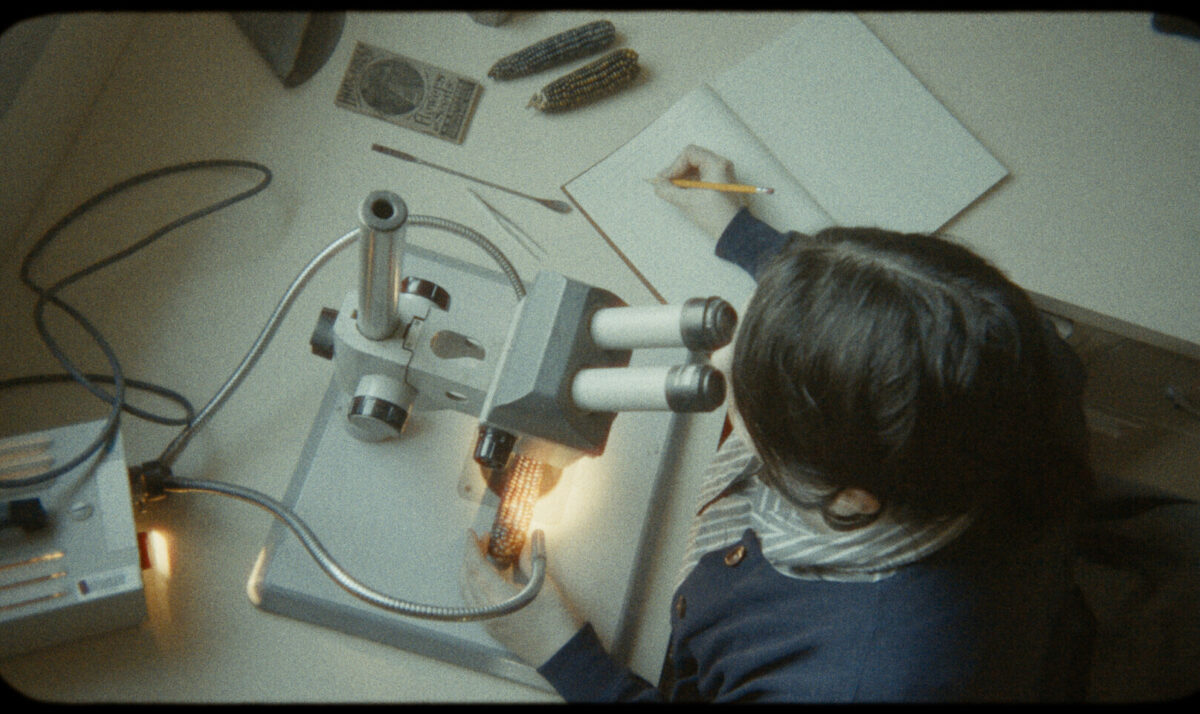

Alexis Gambis: My background is both in biology and filmmaking, and during my PhD, I became fascinated by the lab as a space for visual experimentation, especially with microscopes. I started the Science New Wave Festival in New York to bring scientists and filmmakers together. Scientists often have artistic sides, and filmmakers can be deeply curious about science, so we wanted to break down those silos.

The festival welcomed all kinds of films — fiction, documentary, animation, even raw visual data — curated around scientific and philosophical questions. Unlike many science films that take on the form of a documentary with talking heads, we wanted to create a mix. That naturally evolved into LABOCINE, which archives these films and builds a community around them. The platform is as much about connecting people as it is about sharing films.

Science and experimentation have always been linked — early cinema was about exploring new ways to see the world, just like science. We're inspired by that spirit. We came up with the idea called the Science New Wave, inspired by the French New Wave. Some of the main ideas are to not be afraid of mixing imaginary with scientific data, to remember the diversity of science filmmaking around the world, and to reject hierarchy: anyone can make these types of films.

So we are primarily a platform, but we host our annual Science New Wave Festival and a variety of science film programs year-long. We just finished our annual event called Symbiosis, where we pair scientists and filmmakers who have never met before. Some are more experimental, some do documentaries, some fiction. The scientists include astrophysicists and protein designers. It's like a hackathon — they become close friends, and sometimes the scientists act or are involved in the music. We're really excited about the six films that came out of this year's Symbiosis. That was a commission from the Simons Foundation, committed to advancing science through a wide range of outreach initiatives that bridge science and the arts.

“Science and experimentation have always been linked — early cinema was about exploring new ways to see the world, just like science. We're inspired by that spirit.”

Was it important to you to bring more science stories to the forefront? Did you feel mainstream media was lacking in this area?

Actually, the more you emphasize getting the science out there, the more you enter into a slippery slope. Our film selection focuses more on those that tell stories. People capture science in many different ways. You don't have to always lecture people about science. That's why the platform is great, because you may have a film that explains string theory or survival of the fittest, and those films complement the experimental ones — they'll speak to each other. It's a curation of films, and every month we have a different topic. I don't worry so much about getting the message out there. We don't want films that are too politicized; we want it to be about people, and about visual language.

I will say that scientists, when they make films, tend to be the most experimental in how they make films. Filmmakers, sometimes, because they may have gone to film school, tend to be more conservative, like making a three-act structure. Scientists are just like, "I don't know, I just have this idea that I need to get out."

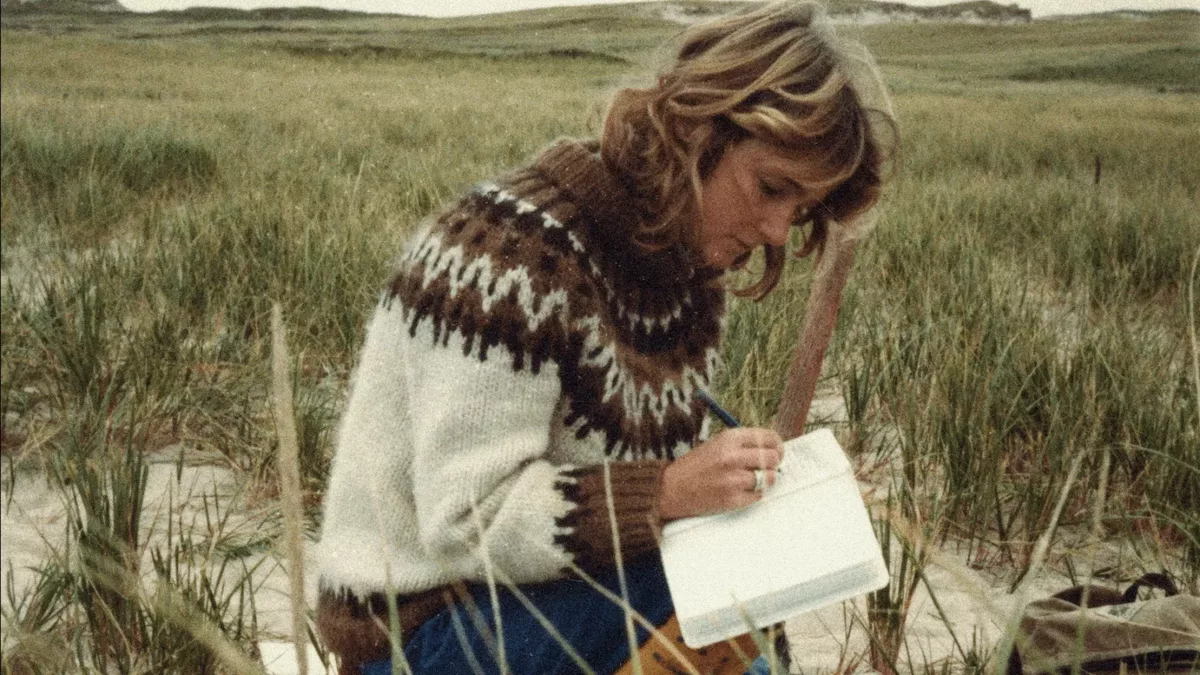

There is a film by Penelope Lindsey and Nora Long about corn. The biologist Penelope created the soundtrack inspired by her research on corn.

We also encourage people to upload notes about their films, through our Field Notes. The film is the main source, but if you're a researcher, it can be a useful tool to learn more. We also have Playlists, where you can create a playlist that may be a reference to help you with your own work — if you're doing research about, for example, forests around the world.

“Scientists, when they make films, tend to be the most experimental in how they make films. Filmmakers, sometimes, because they may have gone to film school, tend to be more conservative, like making a three-act structure."”

LABOCINE seems to celebrate both the art of film as well as the art of science — and to invite professionals of both practices to experiment.

Exactly. It’s also about accessibility. Anybody can do it. Sometimes, platforms like National Geographic and Discovery become a little intimidating, and people say, 'I don't know if I can make a science film.'

I love those films; I'm the first one to watch a beautiful film about butterfly migration. But accessibility means you can be anywhere in the world and have an idea for a music video about pollution, and make it. We're very interested in inviting everybody to be part of it. In some ways, we're also trying to change the way streaming in general happens. There are big players out there like Netflix and HBO, and we're trying to find ways in which some of these works that don't get distributed have a home. So many films don't get distributed — but if they're part of a curated collection, they get a new life. We're also interested in films that are a little bit older, bringing back films made five or ten years ago.

“There are big players out there like Netflix and HBO, and we're trying to find ways in which some of these works that don't get distributed have a home. So many films don't get distributed — but if they're part of a curated collection, they get a new life.”

Would you mind sharing a little about how LABOCINE is funded?

Before we created LABOCINE, we were a nonprofit. We relied on grants and funding from foundations and philanthropists interested in science communication. I ran the festival for over 15 years and realized it wasn't sustainable. In the US, a lot of funding is being cut, especially in the arts. So I came up with the idea to create a subscription-based model. If you join LABOCINE, there are monthly and yearly plans — $3 a month or $30 a year. The idea is that the community helps support the platform, and that money is used for programming and licensing films. If you're contributing work, we pay you. We usually license films for a month because we do monthly issues.

The other revenue mode is organizational. If you're a university or museum and want access to LABOCINE for a classroom or an exhibit or event, you can get access to the entire library. You pay depending on how many people need access, and we help curate. If you organize an event, we also give back to the filmmakers. For example, if a museum is interested in organizing a children's program and your film is selected, we act a bit like a distributor in that sense. In many classes now, students are learning about climate change — why not show them films made by artists from around the world?

Is most of your content acquired or commissioned?

For the most part, it's acquired. We receive films through a submission portal and review them. If approved, it goes onto the platform privately, so you have access, but it's not yet featured. Then you can decide if you want it accessible to everyone. We then program monthly issues and invite filmmakers to be part of a specific month's curation. People get excited to be part of a curated collection. Their film may already be in our archive, or we bring it in and feature it. When we invite a film to be part of our programming — whether it's the annual festival or a monthly issue — we pay a fee or honorarium for that film. We're growing as a platform, so we don't have huge resources, but as we grow, we can compensate more.

We're starting to do original productions. For example, we've been asked to make something about marine ecosystems in different countries. When we make films, we bring in people from LABOCINE who fit the spirit of the platform. It's not a traditional documentary — it might be experimental, shot on 16mm, and visually unique.

Could you share some of your favorite films featured within the LABOCINE ecosystem?

There's an Argentinian film called Herbaria, which is about preserving plants and the preservation of cinema. It was made by Argentinian filmmaker Leandro Listorti, who is also an archivist and a projectionist. It's a beautiful film that was part of our Plant issue called Ethnobotanica. That was one of our most popular issues ever. Everybody is interested in how to film plants and preservation.

Last Things and De Humani Corporis Fabrica (features) as well as An Impression of Everything and Bleu Silico (shorts) From our June issue called MICROGRAPHIA are both lovely and really represent the range of films we have from sci-fi, to documentary to experimental and also from various parts of the world.

How do you envision LABOCINE evolving, to keep supporting independent science filmmakers and foster cross-disciplinary collaborations?

I never got into this with an entrepreneurial mindset, but in some ways, I've had to take one on as we build LABOCINE. What's interesting is that as you start growing, you realize your audience meets you as well. It's not just about deciding the direction yourself; sometimes you realize there's a big interest in a certain area. What's amazing is that we've been able to retain our independence. We're not in a situation where investors or others tell us what direction to go. That's a fear I have — that someone comes in and wants us to do more documentaries or talking heads. So we have a little freedom in where we go next.

I think the next direction is making our own films — original productions using our own community. We want to identify people and say, "We want this filmmaker and this person, and we want to do a series about cats," or whatever the topic is. (We're actually going to do a whole month on cats – we have films about the future of radioactivity where they're thinking about having cats as the ones that warn us about the future!)

The other idea is growing the Scenes section of the platform. Scenes are small clips from scientists and people experimenting with ideas, but they don't really call them films; it can be ten seconds of footage. We want to grow the Scenes part as an archive of material that others can see and maybe collaborate on, eventually making a film together.

Of course, our main focus right now is the monthly issues and the annual festival, and those will continue. But those are the two big things we're trying to grow. Maybe eventually our community will propose events, so we no longer program everything. Someone might say, "I want to organize a Science New Wave event," and we could help facilitate.

I love that the LABOCINE space feels playful and experimental. You don’t have to make a high-budget masterpiece in order to be featured and you can explore new ideas and avenues and gauge how they resonate with an audience.

Filmmaking is hard, and it's even harder to make a living as a filmmaker. I went from doing a PhD in biology to film school, so I know how difficult it is to make films and get funding, and then actually make a living. We need to rethink the many ways of making and showcasing films. That's why I created LABOCINE — as a way of creating a home, because I realized I wasn't the only one feeling that way. It was a way of bringing people together and showing how many ways there are to make films. Science cinema is also about experimenting with film, and some projects have big budgets while others are small home experiments. Bringing it all together without hierarchy is important.

“We need to rethink the many ways of making and showcasing films. That's why I created LABOCINE — as a way of creating a home, because I realized I wasn't the only one feeling that way.”

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.